Recenzje (886)

Bullet Train (2022)

Bullet Train can be criticised for a lot of things, but it can also be enjoyed for the same reasons. Here we have Japan literally on a high-speed train together with a furious pace and non-linear narrative that rather serves to divert the viewer’s attention and mask the screenplay’s shortcomings, as well as the simulation of depth and reach typical of the source material’s author, Kōtarō Isaka. Unlike Japanese adaptations of Isaka’s novels, here the motifs of interconnectedness, luck and fate do not evoke wonder and pathos, but are ground down into superficially entertaining attractions. Bullet Train also works with Tarantino-esque characters, i.e. absolutely unrealistic genre characters that stand out due to their exaggeration, stylishness and grounding in pop culture. Based on the described principle, Tarantino and some of his disciples create sophisticated, powerful and seemingly well-thought-out gangsters and killers that, in the best case, transcend the level of the wet dream of fictional perfection and become semi-divine ideals that viewers admire. In Bullet Train, however, they just remain unrealistic, amusing puppets with one cartoonishly exaggerated and endlessly repeated attribute. Then we have the action scenes, or rather their choreography, which was at the forefront in previous 87North (or 87Eleven) productions, drawing attention to itself through spectacular physicality, difficulty of execution and revolutionary ingenuity. This time, the action is rather in the background, always primarily in the form of slapstick gags connecting the individual plot sequences. Whatever overarching term we use for the film’s described tendencies – bastardisation, anti-sophistication, dumbing-down, assimilation or Hollywoodisation – this is what gives Bullet Train its charm and effectiveness. The film absorbed into itself every possible trend of previous years and even decades that had been valued by overly clever fans, cinephiles and devotees of alternative niches, and strained them through the mainstream filter to create a universally accessible form. It will inevitably be derided by the elites because it is not like the perfect forms that they appreciate, but it will make Bullet Train a popular box-office hit. After Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw, Leitch’s subsequent project evokes the middle-of-the-road works of Hong Kong cinema’s golden era, which comprised chaotically disparate variety shows blending together a multitude of emotions and genre positions, and where the audience’s attention was constantly drawn to various attractions, including action escapades and cameo appearances by popular stars. If we recall that David Leitch and his contemporaries are great admirers of Hong Kong movies, it’s possible to see this not as a coincidence, but as a concept.

Kaza-hana (2000)

Unfortunately, Sōmai’s last film now seems like, among other things, the antithesis of the Oscar-winning Drive My Car. Instead of a red Saab, we have here a pink Jeep, and instead of an uplifting treatise on pain and the cathartic relief of sharing it between characters from artistic circles, we have the openly destructive self-torment of a drunk and a prostitute, to some extent evoking Leaving Las Vegas. At its core, however, Kaza-hana shares with Hamaguchi’s hit the motif of the past as a path that winds behind us, as well as the pain and injustice that can cause us to stagnate on that path. In line with the original title, which refers to tiny snowflakes flying in the wind, the film’s characters are also buffeted by their circumstances and surroundings, though at their core they are fragile and sensitive, as well as imperfect. In Kaza-hana, pain is simultaneously a burden for the characters, dragging them to the bottom, and paradoxically a motivation for their journey, whose destination they have forgotten, but which nevertheless hangs bitterly over their heads. The non-linear narrative not only depicts the stories of the central mismatched duo, but also helps to inject into their tragic journey a sense of exaggeration and playfulness that gives them a believably human dimension. We can only speculate as to how Sōmai’s signature style would have evolved in the years to come if the director’s career not been cut short by cancer. In Kaza-hana, we find all of his trademarks (long shots, a subjective soundtrack, the natural elements as an expressive framework for emotion) used in delicately restrained form so that they completely serve the nature of the scene and draw minimal attention to themselves.

The Legend of Billie Jean (1985)

No one can preach about non-conformity and cool rebellion against a rotten system as convincingly and intoxicatingly as the rotten system of conformist Hollywood studios. In some respects, The Legend of Billie Jean is generally likable and progressive – particularly as a flick for teenage girls that isn’t afraid to include talk of menstruation and thematise harassment by sleazy older guys. It is not entirely appropriate to criticise the film for its lack of cohesiveness, as the filmmakers clearly wanted to evoke certain feelings rather than build a standard narrative. This approach enabled them to step back from causality and logic at key moments and build, for example, an impressive music-video sequence illustrating the title character’s growing legend. On the other hand, the naïveté of this and other sequences in the second plan reveals the film’s dubious core. It preaches queerness only within the boundaries of decency and traditional gender norms and roles. Instead of fully attacking more fundamental and systemic problems, such as harassment and the roles predetermined for girls in society at the time, it focuses attention on the banal details and the captivating charm of Helen Slater with her cool tomboy haircut.

Ex Machina (2014)

A gender chess game for four players. Eight years after its premiere, and in the context of Garland’s two subsequent films, Ex Machina has proven to be not only a shining directorial debut, but also a curse. Based on this film, Garland, who served as both director and screenwriter, has been inappropriately pigeonholed in the sci-fi and fantasy genre. As in his later films, however, the genre is merely a stylistic framework not for reflections grounded in science fiction and fantasy, but for interpersonal and relationship contemplations. Garland is fascinated by artificial intelligence as a field that mirrors gender issues, particularly in the sense of consciously and unconsciously stylised performance, as well as the observation, adoption and use of roles or codes that underlie most human interactions, even though they are artificial and unnatural at their core, or rather they are not inherent to our unique personalities. At the same time, Ex Machina examines the objectification of women and the extent to which we perceive the real personality on the other side of interpersonal interactions between members of the opposite sexes or, conversely, whether we merely project gender codes and patterns onto the other’s personality. It’s actually not surprising then that, on the one hand, the film is enthusiastically embraced by geeks who see themselves as Nathan, even if they are rather Caleb, while on the other hand, some paradoxically accuse it of sexism and objectification based on an interpretation that is equally limited and blind in principle.

Hikaru onna (1987)

Thanks to Sōmai ’s expressive style and ambitious directing, this kitschy story of innocent simpletons in the rotten big city takes the form of a magnificent symbolist fairy tale that amplifies the naïveté and theatricality of the story, while also transforming it into a captivatingly fascinating fantasy. The questionable corners of Tokyo and the gallery of eccentric outcasts that inhabit them are transformed into romanticised caricatures that enchant the viewer. The high and the low blend together here in hyper-aestheticised operatic surrealism, a full range of genres mix without inhibition and raw, pure emotions rule over everything. In other words, Sōmai created, in a Japanese setting, an equivalent of the French cinéma du look movement, or rather one element of it, represented by the big-city fantasies of Leos Carax (actually his whole filmography), Jean-Jacques Beineix (Diva, The Moon in the Gutter, IP5: The Island of Pachyderms) and Luc Besson (Subway). If we develop the line of thought on the side of cinema as a mutually enriching dialogue between films and filmmakers, we can see reflections of Sōmai’s Luminous Woman not only in Carax’s phenomenal The Lovers on the Bridge released four years later, but primarily in the generation-younger major project and generational cult film Swallowtail & Butterfly, whose director, Shunji Iwai, and Kiyoshi Kurosawa have been cited as the filmmakers who appear to have taken the most inspiration from Sōmai’s work. In his film, Sōmai transports viewers to the world of illegal wrestling, but in a fantastically stylised form in which the circus, jugglers and opera come together alongside wrestling, all watched by an audience dressed in formal wear. Here he develops a romantic triangle involving a simpleton from the countryside who has come to Tokyo to find his fiancée. As he finds out that she has irretrievably surrendered to the enticements of the big city, he becomes close to an opera singer, whose heart he must win from a villainous illusionist. As in Lost Chapter of Snow: Passion, Sōmai stylises the whole narrative in spectacularly artificial vignettes, thus enhancing the fantastical nature and unreality of the narrative. In addition to the pastel colour filters and his trademark long dolly shots, he makes maximum use of the layout of the setting. In the exteriors, he plentifully shoots long sequences on the streets without restricting the passers-by, thus using their authentic reactions to draw attention to the staged action in front of the camera. The interior sequences are almost downright theatrical, with ingenious sets that add additional image plans through movement of the camera and the scene. After all, it is not only in this respect that Luminous Woman has another parallel in Francis Ford Coppola’s unjustly ignored musical experiment One From the Heart, which is also distinguished by identically spectacular, fascinating, alienating and difficult techniques.

Terror 2000 - Intensivstation Deutschland (1992)

At first glance, Schlingensief’s typically hyper-exalted circus act may seem like pure madness. But thanks to the fact that it abandons the traditional style and norms of the mainstream and revels in the cartoonishly exaggerated, carnivalesque bustle of the underground, it can focus on a range of phenomena from the end of the millennium. Actually, we can even say that thanks to the style described above, in Terror 2000 he achieved the format of anarchist hypertext, which can encompass in one frantic mishmash not only migration, the rebirth of the Nazis and the bureaucratic apparatus, but also the full range of emotions elicited by the media image of contemporary reality. The film’s central storyline consists in sensationalist and hysterically distorted reporting, which completely abandons the realm of serious journalism and allows itself to be swept up in the mass hysteria that it provokes and feeds. The film does not present this directly through the literal inclusion of reporters, but primarily at the level of style and references. Specifically, the narrative frames the issues of the 1990s in a common storyline with the nationally watched Gladbeck bank robbery case in 1988. The final part of Schlingensief’s trilogy about Germany thus shows the reunified country as a cauldron of hatred, frustrations, obsessions, traumas, racism, violence, helplessness and politics. Schlingensief brings to the aseptically refined German cinema of the turn of the millennium the sorely missed stimulating physicality that characterised genre film production of the 1970s and, in particular, the parallel anti-wave that defined itself against the pretentious New German Cinema. Unlike distinctive filmmakers of the time such as Roland Klick and Klaus Lemke, Schlingensief – remaining true to the underground and alternative theatre – did not look to French or American cinema for style, but instead simply enjoyed exposing viewers to phantasmagorical puppet theatre packed with provocative stimuli. Actually, it’s almost amazing that, in these exalted and exceedingly volatile times, Schlingensief’s films still seem frantic and difficult to grasp. We can find the reasons for this in the way the current online hypermedia suppresses physicality, or rather only allows its refined and standardised form.

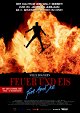

Feuer und Eis (1987)

Fire and Ice is a remarkable experiment that doesn’t quite work, but that doesn't detract from its ambition. To a significant extent, it was a transitional film for Willy Bogner. On the one hand, much of the unbridled playfulness of his previous two goofily disjointed feature-length projects, especially their completely anarchic approach to traditional narrative norms and mainstream cinematic logic, still remains. At the same time, however, Bogner’s ambition to give as little space as possible to standard narrative in his films, constructing it by means of causally interconnected peripetias leading from point A to point B, is fully crystallised here for the first time. In the eyes of the enthusiastic director, cinematographer and headstrong screenwriter, this only takes space for real, purely physical attractions that superficially inspire awe. Bogner thus logically came up with the concept of a skiing musical, which, in line with the traditional Hollywood model of the given genre, would have only a loosely constructed story that would offer an opportunity for extravagant dance/sports choreography. The result is an appropriately nonsensical farce about a skier who is infatuated with a female skier, and he can’t keep his mind off her and skiing as he follows her trail across America from New York to Aspen. The framing of the individual sports passages, such as the protagonists’ fantasies, makes it possible to come up with completely phantasmagorical sequences aimed at maximising the aestheticisation of various winter sports, as well as their summer variants, while also enabling their adrenaline-fuelled practice outside of the traditional spaces intended for them. This was also Bogner’s first project with obvious product placement of brands other than his own, as well as the beginning of an explicitly targeted search for experts in new outdoor or extreme sports and recording their wilderness venues for a broader audience. The film thus has primacy as the first feature film depicting snowboarding, as well as some other disciplines that were still not being practiced at the time and attempts at those disciplines, such as the combination of snowboarding and windsurfing. With its intentional inconsistency, the film also offers a tremendously diverse range of attractions, from pure music-video sequences of skiers doing synchronized flips in differently coloured jumpsuits, to typically Bogner-style sequences of skiing on a bobsled track and slapstick gags, to a breathtaking ski chase through the streets of a mountain town, filmed by Bogner himself practically in one take, and on skis. In and of itself, Fire and Ice in many ways remains a fascinatingly nutty experiment with genres and the possibilities of film narrative in the context of the cinema of attractions. Nevertheless, within Bogner’s snow-packed braincase and its cinematic imprint, it is only the first small step toward the perfect form of the overall concept of the outdoor musical that he would achieve in his later White Magic.

Juki no danšó: Džónecu (1985)

Variously released under the English titles Stepchildren and Lost Chapter of Snow: Passion, this film is often praised in Sōmai’s filmography for its opening 14-minute one-shot sequence. In this tremendously difficult dolly shot, the entire life story of the central poor orphan girl is told in a stylised studio set. Unfortunately, the rest of the film, though also formalistically impressive, is a bizarre paedophilic melodrama that comes across as a cheesy soap-operatic version of the exploitation fantasy Perfect Education. In the worst case, the film can be seen as a reactionary response of the Tóhó studio, or rather of Marumi Sasaki, the author of the popular book on which the film is based, to the emancipation of women and their abandonment of traditional roles and models of behaviour. Thus, the underage protagonist is no Lolita, an active temptress who seduced men, but rather a supporting character who behaves that way and comes to an appropriately tragic end. Conversely, the protagonist represents the absurdly passive ideal of the traditional woman, devoid of any personality, whose existence is entirely shaped by men and is endlessly subordinate to them. Like all Japanese Lolitas, she comes across as a tabula rasa who is confused by the world around her and terrified by the idea of setting out on her own, which of course means she needs to take care of the men around her. The film’s mainstream narrative understandably celebrates pure love without physical desire, which – though it is present beneath the surface – is not supposed to be fulfilled because it is vulgar, after all. Taking a more lenient view, Lost Chapter of Snow: Passion is a colourful melodrama about an adopted girl who, as her seventeenth birthday approaches, is confronted with having to step out of her adoptive father’s kind-hearted home and into a bitter and cynical world. On the other hand, in line with the unrealistic nature of the premise, Sōmai lets his characteristic one-shots accentuate the unnaturalness and almost Brechtian detachment of the scenes. He stylises them to the point of being kitschy with lyrical and thus artificial vignettes, and even frames the entire film as puppet theatre.

Tókjó džókú iraššaimase (1990)

Shinji Sōmai began his directorial career with hits that fell into the category of idol films. These were projects that were made primarily for the purpose of presenting young celebrities with the aim of infatuating the audience and helping to establish the given idol as a multi-talented performer who would not only appear on camera, but also sing a single on the film’s soundtrack and have her face adorn all promotional materials. Within its category, Tokyo Heaven is a surprisingly self-reflective work whose narrative directly thematises the calculated and prefabricated nature of the idols and their absolute detachment from real life. The main protagonist is the 16-year-old celebrity Yuu, who is on the verge of a great career but dies on the eve of the launch of a major media campaign. In the afterlife, she gets a chance to again walk among the living. She gets around the condition that she cannot return in her own form by requesting the face from a billboard with a publicised version of herself. Coincidentally, she ends up in the apartment of a rank-and-file employee of a PR agency, the solitary Fumio. But the afterlife has a few more rules that Yuu can’t circumvent. Besides not appearing in mirrors and photographs, she mustn’t come into contact with anyone who knows her or knows that she’s dead. The film abounds with a full range of playful and imaginative elements that are variously based on these rules. In terms of execution, the most rewarding of these is the character of Yuu’s guide, the dopey “Cricket”, who takes on the form of the last person Yuu thought of before she died, who happens to be her sleazy, perverted boss. Unlike other films with a similar premise, Tokyo Heaven’s narrative doesn’t revolve around the protagonist trying to right the wrongs of her life or seeking revenge for her death. On the contrary, the ambiguity of her new beginning is variously thematised, placing on the girl the burden of her severed ties with the past, but also the pleasure of an ordinary life and growing up that she did not have in her career as a star. In addition to the straightforward dramatic situations, Shinji Sōmai also expresses these central motifs in several of his typical passages, where hyperrealism is intertwined with metaphors and symbols, which are the highlights of the film (the playground scene after the passage involving the secret visit to her parents’ home, the brilliant one-shot capture of a shadow, and the magnificent sequence with the birthday bouquet). Though Tokyo Heaven is primarily a coming-of-age story about a protagonist who gets a chance to experience life at least for a moment, it doesn’t limit itself to being a run-of-the-mill celebration of fleeting beauty. It presents influencing someone else’s life as the fulfilment of life. That someone else is Fumio, who personifies a typical employee of the given era. The Japanese economy was in the final stage of its boom, or rather its artificially inflated bubble. It burst a year after the film’s release, which brought not only the economy to its knees, but also the system of stable jobs and the existential security of the middle and upper classes. The film was thus actually very prophetic in its message that one should overcome the burden and fear of stepping off of one’s predefined life path and instead redefine oneself according to one’s own personality. Tokyo Heaven is a rather forgotten and obscure title in Sōmai’s filmography. Of course, it offers the pleasure of the director’s typical trademarks, particularly his ingenious one-shot scenes and dolly shots. But it is also surprising as a reminiscence of Sōmai’s creatively wild beginnings and coming-of-age movies. Despite its numerous bizarre fantasy elements, however, Tokyo Heaven remains at its core a melancholic story of two souls who meet and mirror each other and grow close, though not in the usual romantic sense, but in the existential sense.

Wszystko wszędzie naraz (2022)

I thought such an unrestrained eruption of creativity was possible only in animation and I’m terribly glad that Dan and Daniel have shown me how wrong I was. On the other hand, no one has ever approached the medium of film with such hyperactive playfulness as they have. While their meta-work is essentially cinematic (in terms of the story being told, the narrative processes and the references), it also personifies the internet in its Web3 phase, with all of its fascinating beauty, pioneering potential, non-linear hypertextual nature and terrifying intangibleness far beyond the possibilities of a single person’s perception. After all, the creative approach of the disparate and yet extraordinarily symbiotic creative duo of Daniels fulfils the principles of decentralisation and blockchain interconnectedness. Everything Everywhere All at Once continues on the path marked out in the field of feature films by the animated movies Spider-Man: Parallel Worlds and The Mitchells vs. the Machines, but its concentration of online popular creativity, both audio-visual and graphic as well as narrative, is breathtaking and rocks the senses by adapting them to the much more production-intensive format of a live-action film. Perhaps it is thus not a coincidence that everything here ultimately revolves around family, though in a completely different and wonderfully imaginative style in terms of family dynamics in relation to the traditional roles of villains and heroes who have to evolve in order to overcome evil. In addition to that, Everything Everywhere All at Once gives Michelle Yeoh the role of her life, in which she puts the experience of all of her previous on- and off-screen roles to good use.