Recenzje (840)

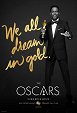

The 88th Annual Academy Awards (2016) (program)

“I is here representing all of them that's been overlooked - Will Smith. Idris Elbow. And, of course, that amazing black bloke from Star Wars...Darth Vader.” We don’t have to like it and we may consider it to be the height of Hollywood hypocrisy, but the times demand a politicised Oscars ceremony. On the other hand, the willingness to talk openly about the problems of contemporary American society (rather than the world as a whole, as was the case last year) has mainly drawn attention away from the inability to address those problems beyond writing a touching song about them (Lady Gaga) or making a high-quality film about them. Though it fit into the overall concept of “Hollywood and liberals for each other” (the words of Adam McKay, a supporter of the far-left Bernie Sanders, aimed at the Democratic candidate, Hillary Clinton, added variety), Joe Biden’s unacceptable performance can be considered the most promising step toward the effective combining of the world of art with the world of politics. Rich white people hurled admonishments from the stage, but pretty much only in the context of friendly banter and pre-arranged bits, and they mainly took home almost all of the hardware. For me, the compromising nature of the evening is best characterised by the speech given by the Academy’s president, who expressed remorse for the lack of diversity in the decisions made by the current member of the Academy, but of course failed to promise any specific changes for the future. In any case, Chris Rock handled his hosting duties with honour, and his jabs were at least aimed in a specific direction thanks to the #OscarsSoWhite movement and were mostly thematically coherent (as opposed to Ricky Gervais’s equal-opportunity insults at the Golden Globes). Louis C.K. highlighted the issue of class differences in line with the content of his stand-up routines, and Ali G hinted at the tone that the whole event should have had (cheeky and to the point, but with a lot of humour). With the exception of the traditional in-memoriam segment, there were no pace-killing collages, the songs served only for variety rather than being performed out of an obligation to introduce everyone (since not everyone was introduced) and the only thing that slowed the evening’s relatively brisk pace was the clips of the nominated films, which were needless for the people who had seen the films and too brief to tell anything to the people who hadn't. With respect to the aspects that were (obviously) prepared in advance, I found the show satisfying. I’m not rating the quality of the Academy’s voting or the accompanying commentary and simultaneous translation of the live broadcast on ČT 2.

Most szpiegów (2015)

Bridge of Spies is a film about America, friendship despite the times and men who are just doing their jobs. Several decades ago, Hanks’s unassuming protagonist would probably have been played by Gary Cooper or James Stewart in a film directed by Frank Capra. As in Capra’s works, in Bridge of Spies American values are represented and defended by incorruptible individuals, not by unreliable institutions. At the same time, the quest for justice leads through so many obstacles and compromises that, at the end, instead of the joy of victory, there is a sense of relief that it’s over. (In addition to that, Spielberg again shows himself to be a master of suggestion and narrative shorthand in the climax, as he makes do with a very simple yet very telling shot of children climbing over a fence. In the context of the previously seen scaling of the Berlin Wall, unsettling cracks thus appear in the façade of the happy ending). ___ Donovan demonstrates his position outside of the system in both halves of the film by following his own rules of the game. He doesn’t act in the way that the people who have given hin his orders think he should act. His concept of justice is not subject to the anti-communist panic, and he makes fun of espionage work (“You know, spy stuff”), not giving it the degree of importance that you would expect from the protagonist of a spy thriller (interrupting a dialogue about the next course of action by telephoning his wife, with whom he sorts out what kind of jam he should bring her from the “fishing trip”). I see as the main screenwriting contribution of the Coen brothers, who, despite all their respect for classic Hollywood, never quite took it entirely seriously (just wait until the premiere of Ave, Caesar! for more compelling evidence) in their subversion of the exaggerated seriousness of a courtroom drama or spy movie by intentionally or seemingly leaving out genre-typical characters and employing down-to-earth catchphrases (“Can we just call them the Russians and save time?”), whose timing demonstrates the intuition of the master. ___ As is customary with Spielberg, the protagonist will have to defend his actions not only to the general public, but also (and, in the end, especially) to his family. Though absent from the latter part of the film, Donovan’s family is both an important motivation of Donovan’s actions (his repeatedly expressed wish to return to the warmth and comfort of his home, which he at least recalls with a hearty breakfast at the Hilton in Berlin) and the source of his doubts as to whether he is a good father to his son and a good husband to his wife. ___ The film’s opening scene, in which we see three different versions of Vogel (live, reflected in a mirror and in a finished self-portrait), aptly introduces us to the world of spies alternating between multiple identities while creating false expectations about the perceptibility of Vogel’s intentions. It soon becomes clear that he is not only a man who maintains an icy calm in all circumstances, but also one of the narrative’s most direct and honourable characters. He even wins over Hanks’s attorney with his sincerity. The special affinity between the two men, who need and influence each other, is expressed in the Berlin part of the film through Hanks’s cold, which forces him to constantly wipe his nose, just as we previously saw the phenomenal Mark Rylance do. ___ The creation of parallels between the individual characters and storylines is one of the film’s strengths, contributing along with the spiral structure of the narrative to its cohesiveness and subverting the black-and-white view of history. The second half of the film (which actually begins exactly halfway through the runtime) is basically a variation on the first half, thanks to which we realise that the two parties to the conflict have more in common than they are willing to admit. The individual shots often respond to each other and, thanks to their smooth continuity, we don’t fall out of rhythm and our attention doesn’t waver. ___ I find it almost needless to praise in Bridge of Spies the elements with which most of Spielberg’s films excel – economical and comprehensible storytelling through imagery and careful management of the viewer’s attention (largely without manipulating emotions – the film is unusually sparing in its use of music, using it for the first time after almost half an hour). Spielberg prepares us in advance with a musical motif, among other things, for the espionage plot, which does not fully take off until the second half of the narrative (the absence of exposition causes the storyline with the suddenly appearing economics student to seem clumsy) and alerts us to what we should pay attention to (“...whether they will embrace me or just put me in the back seat”). He expresses the dominance of one character or the other by their position in the shot, illustrates the thought process or the rebuttal of an argument with a counter-argument through appropriate camera movement, and completes the atmosphere with different colourways for the (warmer) West and the (almost colourless) East. Though 90% of Bridge of Spies consists of scenes in which two old men sit at a table and converse at length, it is every bit as gripping and suspenseful from start to finish as films based on ceaseless action (such as Mad Max). 85%

Pokój (2015)

As in her book, Emma Donoghue thoroughly sticks to Jack’s perspective. Whatever he doesn’t see and hear, we don’t see and hear. In addition to perceiving all of reality through the boy's eyes, we also hear his off-screen commentary, which, though it helps us to understand what makes the unalluring room magical for him, also betrays the book-based origin of the story. ___ The film does not try to shock us with explicit details of the characters’ suffering. By leaving a lot to the imagination, it puts us in a situation similar to that in which Jack finds himself. Unlike Jack, however, we quickly find out that Nick, for example, is not a kind uncle, but a heartless monster. Besides the limited breadth of our knowledge, which at first is comforting and later disturbing, the intertwining of the camera’s perspective with that of a five-year-old boy is manifested by shooting from the level of Jack’s eyes (we usually see the adults from below). Thanks to that, some of the characters and objects seem more terrifying or more mysterious than they actually are and the sudden “change of scale” in the second half of the film, when the camera level rises for the first time, is as stunning and liberating for us as it is for Jack. ___ The room itself, which seemed like an endless magical kingdom thanks to the editing, music and lively camerawork, becomes just an ordinary room. The second half of the story also has far more dramatic potential and emotional intensity than the first half, which in retrospect comes across as a stiff, needlessly long and perhaps gratuitously cruel prelude. Suddenly there are many more directions that the narrative could have taken. Despite expectations, however, the new sources of tension and conflict do not originate in the crime-thriller genre, but in psychological (melo)drama. ___ However, prioritising emotional conflict over external action is sufficiently justified by the continuous drawing of our attention to the bond between mother and son, or rather the ability to adapt our emotional ties to the environment in which we live. Together with Jack and Joy, we gradually realise that the world that they have created for themselves was not bound to a particular place. They carry it within themselves and are unable to leave it. The question of whether they can handle living outside of their room, or allowing someone else into it, thus becomes crucial.___ Whereas on a basic level Room suggestively evokes, with the aid of the smallest physical details, the situation of a person in captivity, we can approach it on another level as a (Platonic) parable about the (virtual) worlds in which we enclose ourselves. ___ Some viewers may be bothered by the fact that Abrahamson does not handle the sensitive subject matter with the cold-bloodedness of, for example, Michael Haneke and does not completely avoid emotional manipulation. On the other hand, he doesn’t make the situation excessively easy for his characters or offer easy solutions to their traumas. The subtly nuanced acting of Jacob Tremblay and Brie Larson significantly contributes to the ambivalent feelings, which ordinary tear-jerkers try to avoid. It is also to their credit that Room works best (and offers the greatest viewing satisfaction) as a maternal melodrama about the fine line between love and hate. 80%

Big Short (2015)

The makers of The Big Short were fortunately conscious of how indigestible a film overloaded with names, numbers, abbreviations and the uncovering of complicated relationships between the individual components of the investment market would be. Therefore, they conceived the film as a two-hour shouting match between a few eccentrics, speaking in advanced economic gibberish instead of human language. Without resigning itself to fidelity to the facts, The Big Short attempts to tell the story as graphically as possible and with the detached humour found in The Wolf of Wall Street. However, McKay is no Scorsese, especially in terms of storytelling abilities. Our guide on the path to economic disaster is Jared Vennett, who occasionally turns directly to the camera or stops the flow of the narrative to gleefully shed light on the tricks that the big fish on Wall Street use. But his own tricks quickly become predictable. The breaking of the fourth wall by the plain-spoken narrator is mainly a means of distraction, not – as in Wolf – an essential part of a well-thought-out narrative strategy. Similarly, the film randomly intersperses the exaggerated comedy with moments of existential crisis for the increasingly helpless Baum (the scenes with his wife are among the most unnecessary of the whole film, which is rather regrettable, given the casting of Marisa Tomei). Also distracting is the hyperkinetic editing and shaky camerawork by Barry Ackroyd, who shoots the sharp exchanges of opinion in the enclosed offices as frantic (Greengrass-esque) action. From start to finish, he zooms, refocuses and pans with admirable energy, resulting in the blending of scenes that are crucial for the narrative with others in which nothing essential happens. Neither the pacing nor the urgency with which the film speaks to us is developed. The film is monotonous, lacks suspense and surprises, and is rather more reminiscent of a PowerPoint presentation than a drama that is funny in places, but you have to force yourself to pay attention to it for the whole two hours. It helps a lot that some of Hollywood’s most charismatic actors vie for our attention; they are excellent especially in the brazenly farcical moments. The partially improvised scenes involving them shouting each other down are among the highlights of the film. Due to the shallowness of their characters, however, they have nothing on which to base their performances during the more serious moments. The same can be said of The Big Short as a whole. As merely a cynical comedy ridiculing people who make million-dollar transactions with no more thought than evacuating their bowels, it is highly entertaining. As a warning against the inherent rottenness of capitalism, it falls flat. 70%

Brooklyn (2015)

Brooklyn is a story from the time when at least the United States welcomed economic migrants almost with open arms and all one had to do to pass through immigration control was to put on decent make-up and smile sweetly. But the film is a return to a bygone era, not only in its realities but also in its straightforward narrative. Compared to the book, it is more sentimental, more literal and less thematically expansive (it leaves out the manipulation of African-Americans and the hint of lesbian love). At the same time, however, it mostly retains the likably unforced development of events and more thoroughly develops the motif of two homes through its narrative structure. In the second half of the film, Eilis experiences similar situations as in the first half, except she is now much more experienced, having risen from pupil to teacher (the transformation culminates in the second scene on the boat, when she advises an inexperienced girl). Green is a constant reminder of home, to which other colours are gradually added, just as other emotions are added to the sadness in the protagonist’s face (instead of one emotion being completely replaced by another). The inability to cut ties to her homeland adds ambivalence to the protagonist’s journey toward fulfilling her dream – during the first hour, she suppresses her sadness, first through concentrated work, then by building a new home, only to be painfully reminded that her real and only home is in Ireland. Thus, unlike other immigration stories, the move to the US is not the end but the beginning of suffering. The boldest departure from the source material is the significant abridgment of the introductory part of the story. In the book, we get to know the environment and the people Eilis will have to leave behind over the course of several dozen pages. In the film, the girl announces shortly after the beginning that she is leaving for America, which she promptly does. Therefore, we don’t have the possibility to better get to know her older and more experienced sister Rose, whose legacy Eilis develops, and thus no tension arises with respect to which of the sisters deserves success and which will ultimately achieve it. Eilis can easily be accepted as a traditional romantic heroine. The film is thus less subversive than the book in relation to the conventions of idealistic narratives about the fulfilment of the American dream. However, it preserves the book’s narrative straightforwardness and its matter-of-fact, unsentimental tone, as it does not simply communicate to us in words and music what the protagonists is going through, but lets us experience it with her. 80%

Vinyl - Pilot (2016) (odcinek)

“Not getting fuck.” It looks like Scorsese decided to apply the delaying tactic from his last film on a larger scale. Multiple scenes in the first episode of Vinyl are reminiscent of the funniest segment of The Wolf of Wall Street (the paralysed DiCaprio), which was long and entertaining, but advanced the plot only minimally as a result. I really don’t know if this retarded narrative was the intention or if its creators only needed to stretch a one-hour plot to twice its length, so they added tens of minutes of verbal exchanges that go nowhere, at the end of which something essential and absolutely unpredictable occasionally happens. Thanks to the feeding of the narrative from several genre sources, it is also difficult to predict the plot twists. This insensitive comedy joyride, which doesn’t spare Anne Frank, ABBA or Chekhov, overlaps with the existential drama of a has-been producer whose descent into darkness and estrangement from his family (which we first learn about after roughly 40 minutes) hastens the shift to a dark crime story. The striking visual references to his earlier films (Taxi Driver, Goodfellas) and the disorderliness of the narrative contribute to the impression of a wild party that Scorsese threw mainly for his own pleasure. Though the point of view of Richie, who introduces himself to us as an unreliable narrator immediately at the beginning, is dominant, it is enhanced by Jamie’s point of view – without contributing to the construction of the story – and in one scene we abandon the protagonist in favour of Devon. The frequent flashbacks (which become more and more frequent as the ending approaches) and musical interpolations serve mainly to rhythmise the narrative, which – paradoxically thanks to the scenes with a long-delayed point – cannot be faulted much. Vinyl’s pilot is reminiscent of an overwrought rock musical. Thanks to the rights to the biggest rock hits, it sounds great and, thanks to the agitated camerawork, it’s never boring because of how it looks, but it doesn’t care too much about the narrative structure and what it is telling us. Perhaps the individual pieces will fit together better with subsequent episodes.

The Scarlet Empress (1934)

The penultimate collaboration between Sternberg and Dietrich gave rise to a somewhat eccentric work which, during its transformation from a studio costume drama into a very European-style and more than a little disturbing fairy tale, recalls the best works of German Expressionism and the (later) second part of Peter the Great. Sternberg again proves to be a distinctive stylist who doesn’t pay much heed to realistic period details or the psychological motivations of the behaviour of the characters, whose gestures are melodramatically exaggerated. He rather pays more attention to the constant contrasts of black and white, where the white in the climax, similarly dramatic as at the end of The Godfather, ironically evokes quite different connotations than at the beginning of the film. The extravagant decorations and props serve as materialised shadows of the actors, whom Sternberg often makes “disappear” among inanimate objects. The protagonist also becomes an object upon her arrival in Russia, but she soon comes to understand how to stand up for herself among the uncivilised madmen. She transforms herself from sexual prey in that she starts to enjoy her humiliation. Played by Dietrich, who lustfully observes both men and women and knows how to precisely serve up ambiguous lines without losing any of their sensuality, this is a very convincing transformation, which is also well “reasoned” by the screenplay and ensures that the film has fans not only among lovers of camp but also among feminist critics. I am neither, but I did not find even a single shot boring. 75%

Porwanie (1952)

Whereas American musicals have Singin’ in the Rain (also made in 1952), the propaganda films of the Czechoslovak Communist Party have Kidnapped. The film’s heavenly prologue, supported by appropriately majestic music, reveals the filmmakers’ considerable ambitions. Later, this “epic” impression is evoked by transferring part of the plot to the grounds of the United Nations. The organisation with a reputation as an international moraliser was also misused for the typically Czech narrow-minded point of the whole film: just let them vote at the UN, and we will vote for what we want at home! And unanimously! Other highlights of this pseudo-spy pseudo-thriller include the International’s singing in unison and the identification of a comrade thanks to his addition of the essential hammer to an abandoned sickle. ___ The bearer of the ideas of the Communist Party is a comrade of the most deliberate kind, deputy Horvát (which is a Hungarian rather than a purely Czech surname, but we are still on the soil of a friendly country, so that’s okay). This member of parliament is decisive and incorruptible, and thus unanimously followed by his true-blue fellow citizens. The narrative formula involving the ideological “cure” of a doubting comrade takes the form of the engineer Prokop. From a “political illiterate” living under the bad impression made by the capitalist world, he is transformed into a man whose head and heart belong to Communism. Others who don’t recoil from bribes in the form of Western food (instead of eating paper with the others) and find pleasure in decadent American culture (Kopecký’s jazz musician) are beyond help. Let them perish in the West! ___ Collectivism, one of the central value norms of Communist ideology, is highlighted throughout the narrative. A Czech (i.e. Communist) is always part of a larger collective and must mainly be careful not to betray the domestic representation, which he can always rely on in an emergency. His interests are transpersonal, motivated by the beneficial effect for the whole republic. Therefore, every gesture carries political weight. Because taking action means disseminating Communist ideals, speaking for oneself and expressing one’s own thoughts would be a betrayal (this is also why it’s necessary to make the apolitical Prokop politically aware). ___ Conversely, the negative characters act of their own accord. They pursue only personal enrichment through their socially irresponsible actions. They necessarily look at the ideological tenacity of the Czech people, who are immune to the American dollar and brute force, with astonishment (“What kind of people are these?”). The capitalists long ago traded all ideals for dollars. Proclaiming “the customer is king”, the capitalist deals with business matters even when he should be invested in his fellow man and his health. Even in his self-centeredness, however, the character representing Western values humbly admits that “your heavy industry is competition for us”. Besides his heightened interest in financial matters, you can also recognise an imperialist based on his devotion to the idea of war. It is necessary to be on guard, because the West is ceaselessly arming itself against the peace-loving countries of the East. The motivation for killing? Money, of course. Among other things, the root of warmongering is the surviving legacy of Nazism (Wanke’s SS uniform coat). ___ The work of degeneracy is completed with comical English (“Okay, boys”) and action scenes peppered with lines like “Lock up, you bastards!” Today we laugh at it, convinced that we ourselves would not be fooled by such transparent ideological manipulation. Or would we? Would it really not have occurred to us somewhere deep in our minds that it’s damned cool to be Czech and always go to the left (or today very much to the right)? Because of such questions, it makes sense to keep an eye on such atrocities, though with a wary sense of amusement, and to examine the mechanisms by means of which the “truth” of a particular group is passed off as the truth of an entire nation. 40%

Zjawa (2015)

In the same way that we talk about the “Hitchcockian” attributes of some thrillers and use the term “Lynchian” to describe weird films, we may soon find ourselves relating the name of Mexican director Alejandro González Iñárritu to movies around which media buzz is artificially created. As was the case with Birdman from the year before last, the hype that accompanies The Revenant is far greater than the attention that the film deserves based on its cinematic qualities. With their respective skills, the dream team of Iñárritu, Lubezki and DiCaprio could have made one of the most powerful adventure movies of recent years. Unfortunately, their straightforward B-movie plot couldn’t be “boosted” by the fluid camerawork, which performs even more captivating tricks than we could see in I Am Cuba (for me, the benchmark when rating films with sophisticated long shots). The story of a man chewed on by a bear, who returns “home” in the manner of Odysseus, is interspersed with mystical dream (hallucination) sequences, dialogue about God reincarnated as a squirrel and manifestations of the devastating nature of unregulated capitalism. Iñárritu, who always takes delight in the suffering of his characters, would be the ideal director for a raw western in the traditional mould, in which violence serves as the main means of communication, sets the action in motion, sets up the plot twists and solves problems. Unfortunately, as pointed out above, he decided to communicate meanings in ways other than through spectacular violence. With words, for example. The use of violence as a central narrative element is justified by its insertion into the unsteady framework of a family melodrama, enchanted by Indian mysticism. I am convinced that The Revenant would have been a tonally and rhythmically more balanced film if it had not so stubbornly pretended to have philosophical depth and tremendous spiritual reach. Unlike in the case of Tarkovsky or Malick, the spiritualism in this film is limited to empty words and unoriginal symbolism. The formalistic aspect is in no way uplifting. Besides the motif of the spiral engraved on the canteen, for example, the cyclical concept of time, which is inherent to the indigenous American population, only highlights the repetitiveness of the protagonist’s suffering. Otherwise, the film has a thoroughly standard structure, with precisely timed twists, conscientious utilisation of all motifs and a satisfying ending that leaves no essential question unanswered. It’s okay for one-dimensional characters to serve as tools for conveying information and pushing the narrative in the required direction, but I don’t think it’s okay if they serve no other purpose, despite the film’s attempt to use them to convince us of its own inventiveness and its commitment to a cause (in this case, the interests of Native Americans; see the documentary about the making of A World Unseen, which is basically very naïve anti-capitalist and environmentalist agitprop). For me, the most fitting metaphor for the film, which outwardly criticises pragmatism but is at the same time supremely pragmatic in the handling of its characters and themes, remains the gif of the lead actor as Hugh Glass buried alive, torn and broken, clawing for his dreamed-of Oscar with his last ounce of strength. 65%

Arrebato (1979)

Even though Rapture did not enjoy a long run in Spanish cinemas and none of the major festivals showed any interest in it, it achieved cult status and became an emblematic work of the Madrid Scene. It is a film made by people with no idea how to make films and how much they cost. Despite that, it looks much more professional and less cheap than anything by Almódovar in the early stages of his career (or rather, the trash aesthetic wasn’t the only possibility for underground Spanish filmmakers). Like other cult movies, Rapture loses a key part of its appeal in an era when even the most obscure cinematic work is generally easily available. Despite that, however, this unconventional vampire flick about the enthralling power of vivid images and other related elements manages to engage even the uninitiated viewer who didn’t have to wait many years to see THIS film. The motif of returning to the past, which was very popular in post-Francoist cinema, was given an extremely subjectivised form here. Though it is somewhat unbearable (someone is always talking in the picture), it disturbingly points out the ease with which earlier events can be rewritten. Whereas José’s flashbacks show what happened, his friend’s recorded commentary in the present puts things in context and connects the present with the past. The protagonist is offered the possibility that makes films so seductive – the possibility to partially take on someone else’s perspective. At the same time, films – together with drugs – multiply the protagonist’s experience of reality. He sees and feels more, he touches immortality, but he is distanced from real human existence. The powerful climax, with a bittersweet reward for José and for viewers eager for the fulfilment of genre conventions, expresses the ambivalent position of Spanish artists, who, with the abolition of censorship (1977), gained unrestricted freedom, the consequences of which were often devastating for them. Abundantly fed with avant-garde currents, Rapture does not offer a manual on how not to drown in the open cinematic sea. However, the fact that the film was finished and that it can enthral the viewer despite its narrative emptiness and sluggishness can be taken as proof that even the non-swimmers – the more foolish and crazier ones – can quickly learned to swim. 75%