Recenzje (840)

Autour de L'Argent (1929)

Autour de L’Argent is the still-fresh ancestor of today’s films about films. Thanks to its creator’s commentary from 1971 (the version available on the bonus disc of L’Argent from Masters of Cinema), this is not only a superbly rhythmised symphony of the production process, reminiscent of Joris Ivens’s early documentaries, but also a very informative resource for students of silent cinema shortly before the advent of talkies. You'll see and hear what lighting equipment was used, how camera operators achieved a regular rhythm when turning the crank, how fade-outs were done and why viewers with lip-reading ability sometimes laughed during serious scenes. However much the then twenty-year-old Dréville mainly wanted to find out everything that could be created with a camera, the film has a head and heel in addition to its poetic and informational value, and it can thus be enjoyed even without knowledge of the work whose creation it depicts.

Szantaż (1929)

Judging from the date of its premiere, Hitchcock’s last silent film, The Manxman, was released to cinemas at producer John Maxwell’s behest after the sound version of Blackmail. The plot bears the obvious hallmarks of a thriller that would later probably be classified as “Hitchcockian”: a blonde damsel in distress, death by stabbing, escape from incompetent cops. The first seconds are reminiscent of the avant-garde urban symphonies by Walter Ruttman and Dziga Vertov – movement, the city, a rhythmic montage. There is no dialogue in the opening eight minutes, when the characters just idly open their mouths. The whole sequence of arrest, interrogation and imprisonment, accompanied only by non-diegetic music, arouses the impression that we are watching a silent film. It’s open to speculation as to whether Hitchcock is thus intentionally toying with viewers’ expectations and whether he is forcing us to wonder when the synchronised sound will finally be heard. In order for the director to make his dispassionate attitude to sound technology even more clear, the film’s first dialogue scene does not deal with anything crucial; rather it is merely unimportant, as if it’s the dialogue of two men recorded in passing. Furthermore, both of the men are filmed from behind, a technique that Hitchcock used to elegantly solve the problem of early talkies with imperfect synchronisation of picture and sound. This is only the first of a number of examples of ways to deal imaginatively with film sound demonstrated in Blackmail. Among other things, the film contains one of the first uses of a sound transition, or subjectively perceived sound (the famous scene with a “knife”). The lead actors didn’t manage to rid themselves of the expressive acting of silent films, but if their acting is more subtle at certain moments, that is primarily due to the use of sound. For example, whistling a cheerful melody is enough to express a good mood, and it’s not necessary to accompany laughter with exaggerated gestures. Whereas other directors considered sound technology a limiting factor with respect to possible camera movements, in Hitchcock’s work there are no apparent limitations given the multi-camera shooting, for example. For Hitchcock, film remains a primarily visual medium. Immediately in the introduction, the film offers an original point-of-view shot through the eyes of the criminal; the characters ascending the stairs are captured by raising the camera to an unusual height, and other shots are also enlivened by various camera movements. In the areas of editing and the mise-en-scéne, two key influences on early Hitchcock, namely Soviet montage and German Expressionism, are combined in Blackmail. Using quick cuts, developments in the Scotland Yard investigation are condensed into a few seconds, Anna’s state of mind during her night-time wanderings around the city is illustrated through deflected camera angles, and there is also some expressionism in the shot when the protagonist passes a crowd of laughing gawkers. Hitchcock didn’t let himself get carried away with the new technological possibilities. He realised the advantages and disadvantages of innovations without losing the narrative techniques of silent films that had been developed over the course of years. If only more directors of that era had followed his shining example. 80%

It (1927)

Based solely on the first impression, Clara Bow plays the dictionary definition of a girl who has “it” and who wants “it” (the concept of the “it girl” arose from this film). She is turned into a sex object personifying That Which Every Heterosexual Man Desires mainly by men who are incapable of accepting her as anything other than a cute imp. A longer-term relationship with such a girl just for fun is unthinkable for them. If she became their wife or the mother of their child, she would lose “it” and would no longer be the unattainable personification of secret desires without her own subjectivity (the id would turn into the ego, if you like). Therefore, Cyrus loses interest when he sees her as a mother (though a fake mother, which he doesn’t know). The rejected Lou returns to her life as an obsessive thought (of “it”), as a bad conscience, in order to take revenge by reversing roles. The hunted newly becomes the hunter. Lou realises that her power consists in the fact that she can refuse what a man desires without being his girlfriend (whether at work, where she receives money from a man for her various services, or outside of it). This is just the mutual recognition that without “it”, they are free, not controlled by lust, not forced to play the expected roles, and capable of a fulfilling relationship. With its ambiguous intertitles, the amount of exposed (female) skin and the open thematisation of sexuality, It is raunchy entertainment that rivals the pre-Code films of the talkie era. 75%

Faust (1926)

An example of German expressionism in all its glory. Monumental sets incorporated into the narrative, psychologising of the characters by means of expressive lighting, the actor’s body as a visual element that creates meaning, and strangely deformed set pieces serving to set the mood. Despite the advanced technical level, with the occasional somewhat exhibitionistic use of tricks, most of my attention was focused on Jannings’ Mephisto. He not only controls the fates of the characters, who – typically for expressionism – lose control over their own decision-making (the unforgettable scene in which Mephisto uses his cape as a theatre curtain), but also masterfully rules over the whole film with his lively eyebrows. He set a heretofore unsurpassed benchmark for assessing the charisma of cinematic devils. First by Kyser in pre-production, drawing from German fairy tales, and during production by Hoffman, drawing from the legacy of German romantic painting, romantic motifs were amplified beyond the scope of Goethe’s play, which is forcefully evident in the one-word climax, whose pathos is nothing to laugh at, as it fits seamlessly into the overall opulence of the film. Probably no one would have come up with a more universal and more urgent message and it is difficult to think of one today. Contemporary viewers would scorn such simplification in a modern epic. Here, however, the poetic point perfectly tops off a great story told in grand style. In my opinion, Murnau succeeded in his attempt to transform “home-grown” material into a global spectacle. 85%

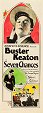

Szczęśliwa siódemka (1925)

This time the natural disaster with which many of Keaton’s films culminate takes the form of approximately five hundred angry women in wedding dresses chasing the protagonist through the streets of Los Angeles. The brilliantly intensified, breakneck stunts and off-the-wall jokes (a turtle!) drive the twenty-minute chase forward, culminating in a scene that leaves the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark in the dust, preceded by a wonderful example of working with time limits. Keaton plays a bachelor who can inherit seven million dollars if he gets married no later than seven o’clock in the evening on his twenty-seventh birthday. That day has arrived and there are only a few hours left until evening. After a girl with whom he has long secretly been in love rejects him because of an inappropriate remark, he tries his luck with seven other ladies. With each rejection, the fateful seventh hour draws closer and Frigo, who keeps a straight face even as he zigzags between rolling boulders, must not stop if he doesn’t want to lose his race against time. Thanks to that, Seven Chances is an extremely dynamic film, enlivened by clever visual gags (which don’t draw too much attention to themselves and leave it up to you to find and appreciate them) in addition to the ceaseless movement of the protagonist, the unconventional design of some scenes (the “static” relocation by car) and the multiple actions running in parallel (the black servant, obviously played a white actor in blackface, is also an unpleasant reminder of the racism of the period in which the film was made). As befits a film of movement, the greatest risk is stopping – the situation becomes critical after the protagonist’s brief nap in the church. Unlike Chaplin’s more traditionalist farces, in which finding a partner also means finding harmony, in Keaton’s film, getting married is essentially a pragmatic decision (or rather a necessity) that is, furthermore, preceded by a series of stressful and life-threatening events. Therefore, the romance of the last shot must necessarily be disrupted by an annoying dog, thus giving us the feeling that no great idyll awaits the newly married couple anyway. 85%

Dziewczęta z Norrtull (1923)

The roles of protagonist and narrator are played by a single woman who is exhausted from taking care of her son and not being able to even buy winter clothes with her salary, as well as from her monotonous job as a clerk, where she is harassed by her importunate boss (the mass scenes of urban commotion and the hustle and bustle of the mechanised office are reminiscent of King Vidor’s The Crowd shot five years later). She finds solace in a gang made up of her three female friends. Together they rent an apartment in Stockholm, where they dance, sing, drink beer and organise a strike for more respectable pay... The “chatty” retrospective narrative in first person rather strikingly reveals that the work on which the film is based was a serialised novel (written by Elin Wägner, journalist, writer, feminist and member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences). By placing the characters in various situations and spaces, director Per Lindberg is able to evoke an atmosphere of closeness and solidarity between the women without using intertitles and in other scenes he skilfully depicts the changing power dynamics, which depend on one’s job, gender or class status. Mainly, it is a joy to see a film from almost a century ago that tells a story of relationships in a social context and celebrates the power of sisterhood. 75%

La Roue (1923)

The Wheel is truly an ALL-EVENING feature film and, at the same time, a textbook of French cinematic impressionism (from which not only other French filmmakers, but also Soviet and Japanese filmmakers would learn the language of film). Made over a period of five years, the monster project cost 30 million francs, its original length was more than eight hours, and its sweeping nature resembles that of a classic novel. Gance, a lover of romantic literature (he referred to himself as the Victor Hugo of the silver screen), shows himself to be a great romantic. He places emphasis on the intensity of dynamic storytelling in combination with the poetic impression of the scenes. He uses soft focus, details that yield meaning, visual symbolism (circles, roses), kaleidoscopic capturing of impressions (subjective shots, rapid montage, juxtaposition, repetition of shots), bold contrasts (unbearable speed x deceleration, city x countryside, dark train x light mountain part), moving cameras, exterior shooting (in, among other places, the Swiss Alps, which may have inspired German mountain films such as The Holy Mountain and The White Hell of Pitz Palu). Thanks to the large number of stylistic techniques, the interweaving of a sentimental narrative with thrilling action scenes (which Griffith usually saved until the end) and the careful steering of our attention, for example by means of various colour shading of scenes (but also thanks to the banality of the main plot and limited number of characters), the complexly structured narrative with a number of flashbacks is never chaotic or tedious. Nevertheless, some scenes of drawn-out agony, testifying to Gance’s sadistic pleasure in the characters’ pain (as a Buddhist, he was convinced that life was suffering), could be shorter. On the other hand, such excessiveness is an inherent part of the melodrama that The Wheel indisputably is, despite the utilised avant-garde techniques (the storytelling techniques are basically conventional due to their psychological motivation and the emphasis placed on emotions). 80%

Blood and Sand (1922)

Blood and Sand is not merely a melodrama energised by the Spanish temperament (some of the lascivious glances would be allowed today only in porn or in a parody). It is also a meaningful self-reflection of the star system. (I don’t know to what degree credit for that is due to Dorothy Arzner, a film editor and director of subversive films about show business, such as Dance, Girl, Dance). If we would like to find parallels between the film’s protagonist and Rudolph Valentino, the story recounting the rise and fall of a toreador is almost prophetic in some ways. Thanks to his body, a young man from a humble background becomes a legend overnight. Loved by children and women, admired by men, he has to face the temptations that accompany fame. His inner conflict is mirrored by the two different women, representing two female archetypes (vamp and Madonna), who come into his life. Carmen spends most of her free time praying and never removes the crucifix from around her neck. Conversely, Doña Sol enjoys seducing and rejecting men and, so that the Biblical symbolism is abundantly clear, she gives her lover a ring in the shape of a serpent. We should most likely believe that Juan has become her victim, that she has made him just as much of an outcast as the bandit Plumitas (this parallel is most apparent in the climax). The film’s moralistic undertones gradually gain strength, coming to the surface in the simple ending, when the moralising point is surprisingly repeated by the character of the intellectual who enjoys writing about human vices. Leaving the last word to the film’s second most malevolent character, who could have easily served as a prototype of some tabloid journalists of the time, gives a strong impression of ambivalence. At the time of the film’s premiere, both the puritans, expecting to be punished for their sins, and the viewers (of both genders), who came to the cinema for the fetishising close-ups of Valentino, could be satisfied and only laugh at the dissatisfied intellectual. Similarly, the whole film can be seen as the simultaneous creation and destruction of the cult of a star. 65%

Zmęczona śmierć (1921)

4-in-1. Four stories differing in style and setting (or rather culture). An old German legend, an oriental adventure, an intrigue-packed Italian drama from the time of the Renaissance, and Chinese comedic fantasy (peculiar also due to the casting of non-Asians in the roles of Chinese). Each story is strongly rooted in the tragic romance of a young couple, but the glue that holds them together is not strong enough in the end. Three tales stand out from the film. Given the time when it was made and the level of cinematic “erudition” among viewers at that time, however, I have to marvel at the boldness of such a narrative experiment. In his use of montage, Lang does not achieve the mastery of Griffith, for example, but he superbly uses the space in front of the camera, the depth, breadth and height of the shots (vertical movement is unusually frequent, but understandable given the theme consisting in the intermingling of the worlds of the living and the dead). The characters run in all directions, thanks to which the picture seems very textured (unlike many theatrically flat films of the time). The stylistically cleaner Metropolis enchanted me more, but Destiny serves equally well as evidence of Lang’s genius (and megalomania). 80%

Rescued from an Eagle's Nest (1908)

An ornithological thriller, thanks to which I finally understood why Hitchcock’s birds are angry and why they’re out for revenge.