Recenzje (538)

Tichije stranicy (1993)

Film communicates with the visual art of its time as intensively as with literary sources - black and white photography, image, and graphics. Sokurov's classic long shots sometimes transform into complete pauses in the film flow, and at that moment, in my opinion, the status of the film changes as well. It's as if, instead of connecting to the narrative tradition of literature, he tries to join the visual tradition of the aforementioned genres (this tendency is stronger in the first half than in the second, where the dialogue of J. Arabov and A. Černik slightly begins to prevail). In the context of the inspiration from 19th-century literature, this means one thing - the film transforms into a book illustration. Indeed, some sequences (freezing into a still image) seem to call out after being torn out from the movie screen and pasted into some sort of Dostoevsky. However, this does not change the fact that Sokurov boldly chose the less known, even seemingly minor (yet important for the period atmosphere) scenes and locations from critically realist literature and transformed them into a unique source of inspiration.

Jauja (2014)

How do you capture the endless expanse of the steppe and how do you fit its width into a film shot? A different filmmaker would probably choose a wide-angle format and a moving camera, but not Alonso. It's as if the awareness of the unattainability of the desert led the author to exactly the opposite approach because the boundlessness of space and time cannot be tamed, but it can be highlighted. This is done precisely by following a procedure where we are forced to observe only a single fragment of the universe with the knowledge that the whole and an even greater beauty than what we see still lies outside. The unattainability of the infinite whole has always forced humanity to choose a single static perspective that was supposed to substitute for the universe - and the filmmaker is similarly forced to put the tripod somewhere. The same applies to time as to space - it, together with the young protagonist, in a figurative sense, overflows through its temporary fragments in history and forces us to see each specific incarnation as a transient form within a broader whole. /// Praise to Alonso and Salminen above all for the fact that their film images are truly beautiful and not kitschy, as they could have easily turned out.

La madriguera (1969)

Switching between the mode of reality and pretense, the invasion of reality into the game and vice versa, and the attempt to leave the game and reach reality. It all starts as a classic psychosis, here in the form of the escape of a frustrated person into the world of fantasy. Only through the non-existent world can the heroine survive the real world. However, fortunately, the film does not end here, but also involves the husband in the game, and with his arrival, the effort to achieve the opposite direction begins, that is, the effort to break free from the game back into reality. At first, the husband pretends to play the game only to help his wife escape from it. However, in the end, both of them get more and more involved in pretending the unreal, and from that moment on, we witness their desperate attempt to break through the bubble of falsehood that surrounds them and crash back into reality. It is paradoxical at first sight that they achieve this only when they physically harm themselves – by spitting, hitting, shooting – as only in this way can the modern person leave their isolation behind, which they definitively abandon only through a definitive act. The most touching is the husband's final contempt for his wife's faked suicide - he would truly prefer to see her die because only then could she reach reality. Saura, as always, has a great crisis – vicissitude - catharsis, but again a lengthy exposition and collision.

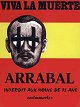

Viva la muerte (1971)

When the opening credits already resemble a painting by Hieronymus Bosch, one must prepare for both fantasy and brutality, in a single blend. A personal, symbolic, and surreal statement about one's own childhood thus blends with naturalism attacking our most intimate senses (not any ephemeral aesthetic abilities), with realism in the description of fascist atrocities. The story of a boy as the story of Spain torn between admiration for the father and love for the mother, where guilt and desire, life and death constantly fight each other - and again (without one side truly winning) come together in a single blend. Therefore, all of Arrabal's film images are predetermined by both desire and death, and the poignancy and dread of this necessity emerge in the person of the mother, whom our protagonist is forced to love despite her guilt – indeed, Spain faced difficult dilemmas in that terrible civil war.

Nippon končúki (1963)

Sternness, rawness? Certainly - but it is also interesting to observe the means by which Imamura achieves this. The film spans several decades, capturing many collisions, crises, and vicissitudes, yet the narrative flows at almost the same pace, uncompromisingly not dwelling too much or too little on any of the subjects. Not only does this relativize their moral status, but it also achieves a detached narrative - the story flows almost homogeneously without interruption, allowing for an exploration of the characters' current inner selves. The film is analytically cold in this regard, keeping only what is essential from the characters' actions, from which their motivations and goals can be reconstructed, and trimming away everything else as unnecessary. However, this is not to say that Imamura cannot capture what is important, quite the contrary. In the end, what remains is just the "skeleton" of human behavior - money, sex, money for sex, or sex for money, trading future prospects for money, trading future prospects for sex. It is a formal finesse that in a film where the narrative does not pause where it "should," the camera and editing pause where they "shouldn't."

Anjo Nasceu, O (1969)

Another one of the fundamental films of Brazilian cinema marginal from the late 60s and early 70s, overflowing with irony, dark humor, rawness, and uncompromising form and content, all against the backdrop of a brutal story about two heartless criminals fleeing across Brazil. Here, just like in the no less fundamental film of this rebellious "movement" - Sganzerla's The Red Light Bandit - we can only rejoice at the combination of the degraded crime genre with a serious (which does not exclude irony and disregard for good morals and conventional expectations, quite the opposite!) statement about the era and society. After all, the total nihilism of the heartless characters (let's not be deceived by visions of an angel - they only signify that heaven is already here on earth, unfortunately) merely doubles the nihilism of the real world. Perhaps the most interesting aspect is once again the formal side, which perfectly fits the label with ease and originality, characteristic of a young creator: the unpredictable uncompromising nature of impulsive characters corresponds to the surprise of the form, sometimes breaking down the wall between the real world and gangsters, sometimes reveling in the aesthetic self-sufficiency of the film camera (which again precisely corresponds to the labeled - the purposeless pleasure of breaking the law alongside the joy of purposelessly long shots).

Żałobna parada róż (1969)

The film is so intertwined with the time of its creation, at least in a formal sense, that it is unnecessary to list all the cinematographic techniques of the second half of the 1960s that the film combines. However, it must be noted that it combines them skillfully and elegantly, a surprising fact for a feature debut. As for the film techniques, one could argue that the obvious inspiration from European and especially French art cinema is perhaps too apparent in a Japanese film. The content is wonderfully intertwined with the form, especially one of the central ideas concerning identity and sight: the LGBT characters, forced to rely on the mediation of sight to establish their own identity (it is their appearance and gaze that (does not) differentiate them from men), are constantly thrown into uncertainty and unreliability of the sense (the explaining scene on the observation tower), constantly aging, constantly resembling men despite make-up, and constantly losing their feminine mask - in short, constantly faced with the unreliability of what we are looking at and how. Essentially, the viewer is also faced with the same dilemma thanks to the use of destabilizing metafictional/quasi-documentary techniques that act as his/her sight.

Amer (2009)

A perfect nod and postmodern mockery of the film genre - this horror-giallo is a tribute to Argento and his essential overcoming: the film is above all clever and its formal aspect is refined to the edge of the best formal mastery, even leaning towards experimental pioneering. The entire de facto silent film is based on the creation of mental associations through visual shortcuts, establishing "short connections" between (contrasting images for the majority of people, not so much for giallo fans...) otherwise contrasting images - death, pleasure, young bodies in the throes of sexuality, wrinkled corpses; (genius!!!) the coquetry of naked skin with synthetic rubber and metal. In short: a constant reversibility of life and death, morbidity and pleasure, achieved through the frenzy of the camera and editing, fetishistic details (substituting for the viewer's touch), and the actual absence of words and a "plot," which forces us to rely on our most lascivious senses sight and touch. This is further proof that films can be told primarily through images! Another question is the reversibility of the victim and the killer, and above all the killer and the viewer, giving birth to perverse film pleasure.

Grabbes letzter Sommer (1980) (film telewizyjny)

The film captures the twilight of the life of the German playwright Christian Grabbe (1801-1836), who in his final years is increasingly sinking into a spiral of contempt towards the hypocritical bourgeoisie society of the Biedermeier era and toward himself. This slide toward human isolation is also increasingly greased by Grabbe's last resort to suppress his disgust - alcohol. The film shows the most irreconcilable conflict between the artist's soul, which, logically, in order to express something new, must criticize and transcend the existing, i.e., what is, and conventional society, which loves the predictability of human behavior, thinking, and feeling. The second painful, although not uncommon paradox, unfolds directly within Grabbe - the rejection of all other people as superficial conformists is in direct contrast to the desire of every artist to achieve recognition, and this can only be achieved through others. This dependence on others, even though he despises them; this contempt for society, against which he is powerless, gives rise to the poignant brokenness of the individual in the era of Romanticism, forced to hate the world and oneself. /// Saless' trademark of long shots and slow pace works well here (although it is not as prominent as usual), but while the extension of shots seemed legitimate to me, the length of the film did not. It is worth mentioning the very good performance of the otherwise unknown Wilfried Grimpe in the lead role.

Pervyje na Luně (2005)

For viewers unfamiliar with Russian history and realities, this film will primarily be a fictional documentary about a Soviet rocket to the moon; for others, it will be a highly original and subjective reflection of the Soviet 1930s. From this perspective, the film operates more on the level of fantasy, drama, and imagination. The illusion of being a documentary and period accuracy may not be as strong as it could have been, but that might only bother the first type of viewers - the rest will enjoy a plastically and only in the style of sci-fi/fantasy elaborate world of alternative Stalinism. When you watch closely, the film is perhaps even more about the overall space program than the rocket and, above all, about what surrounded it: human destinies against the backdrop of secret actions and NKVD espionage, as well as the tremendous tension and enthusiasm of the generation of that time. The 1930s are portrayed by Fedorchenko as both cruel and touching, with the typically Russian attention to the absurdity of human fate. Secret police officers burning documents of the supposed Russian moon landing that everyone believed did not happen, while it "actually" did occur - what could be more paradoxical? Fedorchenko uses fictional film psychotherapy to come to terms with the trauma of his nation, namely the fact that the immense efforts of the interwar generation were betrayed by the Stalinist system and forgotten.