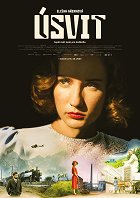

Reżyseria:

Matěj ChlupáčekScenariusz:

Miro ŠifraZdjęcia:

Martin DoubaMuzyka:

Simon GoffObsada:

Eliška Křenková, Miloslav König, Milan Ondrík, Marián Mitaš, Luboš Veselý, Martha Issová, Ladislav Hampl, Ján Jackuliak, Anton Šulík ml., Richard Langdon (więcej)VOD (1)

Opisy(1)

In the 1930s, a pregnant doctor must navigate a web of superstition and prejudice while seeking the truth about a shocking find at her husband's factory. (Netflix)

Materiały wideo (4)

Recenzje (8)

I would very roughly describe We Have Never Been Modern as a period detective melodrama, but it cannot fulfil any of the characteristics of that genre, because it is a film with a fluid genre identity. This corresponds to one of the film’s central themes, which is the inconstancy of gender identities and social roles, as well as the impossibility of incorporating certain facts into familiar frameworks and categories. Though the story takes place in the 1930s, its strength lies in something that isn’t often seen in Czech period dramas – it clearly relates to problems that are relevant to the present. The essence of the film is not the black-and-white struggle against Nazism or Communism, but rather the current feeling of anxiety caused by a society that is only outwardly modern while it allows the restriction of human rights and individuality under the pretext of rationalisation, automation, security, economic growth and building a better tomorrow. If we wanted to identify a villain in the narrative, it’s not the state or the group representing a particular ideology, but the company and its capitalist logic based on thoughtless expansion and exploitation. This is connected with the key theme of the clash between tradition and modernity, where it is again shown that even though we have state-of-the-art production processes, that doesn’t help us much if there isn’t any progress in the thinking of people who cling to certain prejudices and stereotypes and who have the need to determine for others what is normal and to tell people how they are supposed to live. The consequence of that is that this emerging better world is accessible only to those who submit to the given norms and fall in line. The intersex character is a threat to the given order and rationality. In how the others treat her, we see an example of the reactions that we can still encounter today. Ridicule, denial and elimination, as well as the effort to ascertain the necessary facts and to understand exactly what it means not to unambiguously be either a man or a woman from the biological perspective. Together with how the reaction of the female protagonist played by Eliška Křenková evolves, the genre of the film also evolves. Mysterious crime thriller, science film, melodrama, social drama… Though I understand that the changes in genre and making the otherwise imperceptible style visible (the animated interlude, Helena’s glances into the camera, the pointing out of how every retelling of events is also an interpretation over which the participants in those events have no control) may be unsettling for some, they are based on what the film thematises, i.e. rebelling against norms, being uncategorisable, deviating from convention. This brings both anxiety and an awakening (or a new perspective on the matter), which is true both for both Saša and Helena, who realises who or what is important to her in life. Just as the film is ambiguous in terms of genre, the characters are not black-and-white. The complex female protagonist, again something quite rare in Czech cinema, is portrayed superbly by Eliška Křenková. Her Helena convincingly transitions between bitterly commenting on the events happening around her and displays of sensitivity, while also imposing on others her idea of what she thinks is right. The clash of different worlds and attitudes is not conveyed only in the scenography or the work with colours, but also in the contrasting acting performance (the informal Křenková vs. the deliberately affected König), as well as in the use of anachronisms (for example, the fact that the characters use modern language), which highlights the parallels with today. Whereas, in the end, Helena looks to the future with legitimate concerns (as we should too), the future of Czech audio-visual art appears to be somewhat more promising with creators such as Šifra, Douba and Chlupáček. Their We Have Never Been Modern is in fact a modern, refreshing film with a well-developed concept that I believe can spur a discussion of issues that should be addressed today.

()

(mniej)

(więcej)

Someone filmed a series that was decided to be only a film in post-production. Actually, I'm a bit disappointed not to rate it higher because its crafty creative ambitions are easily justifiable on a European scale, but the development of the plot on multiple fronts only leads to a satisfying conclusion in one case (the marital dispute on the staircase, where the perception of the characters is completely turned around, is a screenplay gem, no debate about it), while each of the fronts deserved to be explored much more. Thus, it remains a cheap crime story from a dime-store detective novel, the building of capitalism on the scale of a newspaper article, and a counter-diversion action from a wet dream of a novice spy. However, the "modern" theme of the film holds up, a bit clumsily but effectively and sensitively, in retro attire. 3 and ½.

()

It's too ambitious and at the same time too weak. It has no particular genre and it is uncertain. Is it a thriller? Is it a crime story? A drama? A period piece? A psychological film? A modern melodrama? Nobody knows, but many viewers applaud it because it's simply different. Some are distracted by the picturesque Tatra Mountains and the setting of the Baťa plant. Other viewers are drawn in by the hermaphroditism and few see how weak the psychological connection between the main characters is, the interactions between the supporting characters are rushed, and although We Have Never Been Modern has successful camera work, set design, costumes, and mask, it only loosely adheres to the reality of 1937. These are actors adjusted to the latest trends of barber shops, jerseys, and hoodies... which are understandable today, but nonsensical in the given period piece. Some details are successful, such as the use of František Krištof Veselý's song, but the whole fails. Whether as a crime, drama, or educational film.

()

It’s a shame that of all the topics raised in We Have Never Been Modern (the Czech industrialist Baťa’s utopia/dystopia, tolerance, the political grudges of the First Republic, women’s standing in society), the film doesn’t really develop any of them and rather merely presents them. Similarly, it awkwardly shifts between the genre layers of an otherwise appealingly constructed story. The film seems as neglected as the female protagonist, whose suspicious “rightness” becomes problematic only in the end. The powerful dilemma is resolved very carefully in the comfort zone of Baťa-style modernism. We Have Never Been Modern proceeds with caution and is a bit clumsy in explaining things (the doctor’s animated lecture about hermaphroditism was the only WTF moment). In spite of that, however, it is one of the most interesting films that Czech cinema has generated in recent years. The attempt to be different and to make a masterfully crafted period piece is quite obvious, but I couldn’t shake off the impression that the film occasionally couldn’t get out of its own way in its effort to not go down the well-trodden paths.

()

For a 29-year-old director, this is an extremely ambitious work with powerful, intimate moments involving an original, socially sensitive subject. We Have Never Been Modern works fantastically in its timeless message about society’s ineradicable narrow-mindedness, prejudice and intolerance of anything different. However, it won’t work for everyone when it comes to the interplay of secondary themes (the problematic relationship between the protagonist and her careerist husband, the disturbing character of the counter-intelligence agent) or by setting it in a planned industrial microcosm. Nevertheless, that microcosm adds to the film’s attractiveness for the viewer, while also giving the story a historical foundation to better underscore the concept. And with the nicely stylized studio sets in the foreground of the High Tatras, it also forms the creative patina of the artistic parable. Though it’s not perfect in every detail, it is certainly something that most Czech filmmakers would not dare to attempt. Matěj Chlupáček is somewhere else and if he follows the same path over the next decade as he did between Touchless and We Have Never Been Modern, his third feature film will receive standing ovations at Cannes and Venice. [Karlovy Vary International Film Festival]

()